The Fluctuating Atmosphere of Jupiter’s Volcanic Moon Io Revealed

Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has a thin atmosphere that collapses in the shadow of Jupiter, condensing as ice, according to a new study by NASA-funded researchers. The study reveals the freezing effects of Jupiter’s shadow during daily eclipses on the moon’s volcanic gases.

“This research is the first time scientists have observed this remarkable phenomenon directly, improving our understanding of this geologically active moon,” said Constantine Tsang, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. The study was published Aug. 2 in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Io is the most volcanically active object in the solar system. The volcanoes are caused by tidal heating, the result of gravitational forces from Jupiter and other moons. These forces result in geological activity, most notably volcanoes that emit umbrella-like plumes of sulphur dioxide gas that can extend up to 480 kilometres above Io and produce extensive basaltic lava fields that can flow for hundreds of kilometres.

|

| In full eclipse, Io’s atmosphere “collapses” as SO2 gas becomes frost on the moon’s surface. The atmosphere redevelops when sunlight returns. Credit: Southwest Research Institute |

The new study documents atmospheric changes on Io as the giant planet casts its shadow over the moon’s surface during daily eclipses. Io’s thin atmosphere, which consists primarily of sulphur dioxide (SO2) gas emitted from volcanoes, collapses as the SO2 freezes onto the surface as ice when Io is shaded by Jupiter, then is restored when the ice warms and sublimes (i.e. transforms from solid back to gas) when the moon moves out of eclipse back into sunlight.

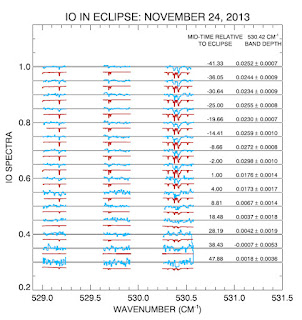

The study used the large eight-meter Gemini North telescope in Hawaii and an instrument called the Texas Echelon Cross Echelle Spectrograph (TEXES). Data showed that Io’s atmosphere begins to “deflate” when the temperatures drop from -235 degrees Fahrenheit in sunlight to -270 degrees Fahrenheit during eclipse. Eclipse occurs two hours of every Io day (1.7 Earth days). In full eclipse, the atmosphere effectively collapses, as most of the sulphur dioxide gas settles as frost on the moon’s surface. The atmosphere redevelops as the surface warms once the moon returns to full sunlight.

“This confirms that Io’s atmosphere is in a constant state of collapse and repair, and shows that a large fraction of the atmosphere is supported by sublimation of SO2 ice,” said John Spencer, a co-author of the new study, also at the Southwest Research Institute. “Though Io’s hyperactive volcanoes are the ultimate source of the SO2, sunlight controls the atmospheric pressure on a daily basis by controlling the temperature of the ice on the surface. We’ve long suspected this, but can finally watch it happen.”

Prior to the study, no direct observations of Io’s atmosphere in eclipse had been possible because Io’s atmosphere is difficult to observe in the darkness of Jupiter’s shadow. This breakthrough was possible because TEXES measures the atmosphere using heat radiation, not sunlight, and the giant Gemini telescope can sense the faint heat signature of Io’s collapsing atmosphere.

The observations occurred over two nights in November 2013, when Io was more than 675 million kilometres from Earth. On both occasions, Io was observed moving into Jupiter’s shadow for a period about 40 minutes before and after the start of the eclipse.

Regarding Io, this is the innermost of the four Galilean moons of the planet Jupiter, and It is the fourth-largest moon, having the highest density of all the moons, and is the driest known object in the Solar System. It was discovered in 1610 and was named after the mythological character Io, a priestess of Hera who became one of Zeus's lovers.

With over 400 active volcanoes, Io is the most geologically active object in the Solar System. This extreme geologic activity is the result of tidal heating from friction generated within Io's interior as it is pulled between Jupiter and the other Galilean satellites—Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Io's volcanism is responsible for many of its unique features. Its volcanic plumes and lava flows produce large surface changes and paint the surface in various subtle shades of yellow, red, white, black, and green, largely due to allotropes and compounds of sulfur. And with a diameter of 3600 kilometres, it is the third largest moon of Jupiter. In Io there are large plains and also mountain ranges

Sources: NASA, Southwest Research Institute, USGC, Wikipedia

------------------------------------------------------------------

Revelada la atmosfera fluctuante de Ío, la luna volcánica de Júpiter

La luna volcánica de Júpiter Ío, tiene una fina atmosfera que se colapsa bajo la sombra de Júpiter, condensándose como hielo, según nuevos estudios realizados por investigadores finaciados por la NASA. El estudio revela los efectos congelantes de la sombra de Júpiter durante los eclipses diarios sobre los gases de los volcanes de la luna.

|

| Size comparison between Io (lower left), the Moon (upper left) and Earth. Source: Wikipedia |

“este nuevo estudio es el primero en que los científicos observan tan importante fenómeno de forma directa, mejorando nuestro conocimiento de esta luna geológicamente activa.” Dijo Constantine Tsang, en el Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. El estudio se ha publicado el 2 de agosto en el Journal of Geophysical Research.

Ío es el objeto del Sistema Solar volcánicamente más activo. Los volcanes se originas por calentamiento de marea, como resultado de las fuerzas gravitacionales de Júpiter y de otras lunas. Dichas fuerzas dan como resultado actividad geológica, y de forma más destacada volcanes que emiten unas columnas de gas de dióxido de azufre a modo de paraguas y que pueden alargarse hasta los 480 km por encima de Ío, y producir extensos campos de lava basáltica que pueden fluir por cientos de kilómetros.

Las nuevas investigaciones documentan los cambios en Ío cuando el planeta gigante proyecta su sombra sobre la superficie de la luna durante los eclipses diarios. La fina atmosfera de Ío está compuesta principalmente de dióxido de azufre (SO2) un gas que lo emiten sus volcanes, que colapsa como SO2 congelándose en la superficie como hielo cuando Ío está en la sombra de Júpiter, para ser repuesta cuando el hielo se calienta y se sublima (i.e. transformación de solido de nuevo a gas) cuando la luna sale fuera del eclipse y de nuevo a la luz.

|

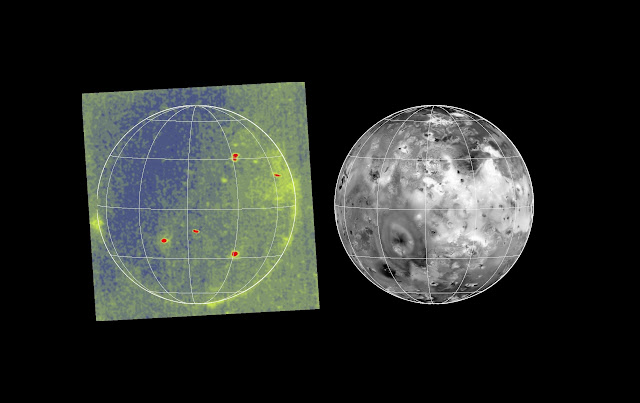

| Io Glowing in the Dark. The image was taken by the camera onboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft on 29 June, 1996 UT while Io was in Jupiter's shadow. Credit: NASA/JPL/Ames Research Center. |

El estudio ha usado el gran telescopio de 8 metros de Gemini Norte en Hawái y un instrumento llamado el Texas Echelon Cross Echelle Spectrograph (TEXES). Los datos mostraron que la atmosfera de Ío comenzaba a “desinflarse” cuando las temperaturas bajaban de -235 grados Fahrenheit a los -270 grados Fahrenheit durante los eclipses. Los eclipses ocurren por dos doras en cada día de Ío (1,7 días de la Tierra). Durante el eclipse total, la atmosfera colapsa de manera efectiva, ya que la mayoría del gas de dióxido de azufre se asienta a modo de escarcha en la superficie de la luna. La atmosfera se vuelve a desarrollar una vez que la luna retorna a la luz.

“esto confirma que la atmosfera de Ío está en estado de constante colapso y reparación, y nos muestra que una gran parte de la atmosfera se nutre de la sublimación de hielo de SO2,” dijo John Spencer, coautor de la nueva investigación, y que está también en el Southwest Research Institute. “Aunque los hiperactivos volcanes de Ío sean la fuente ultima de SO2, la luz solar controla la presión atmosférica de manera diaria a través del control de la temperatura del hielo en la superficie. Hace tiempos que sospechábamos esto, pero por fin lo hemos visto suceder.”

|

| Global image of Io in true color. Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona |

Anteriormente a este estudio, no se pudo ver la atmosfera de Ío de forma directa en un eclipse dado que la atmosfera de Ío es difícil de observar en la oscuridad de la sombra de Júpiter. Este avance ha sido posible porque el TEXES mide la atmosfera gracias a la radiación de calor, y no la luz solar, y que el gigante telescopio Gemini puede percibir la débil señal del colapso de la atmosfera de Ío.

Las observaciones tuvieron lugar durante dos noches en noviembre de 2013, cuando Ío estaba a más de 675 millones de kilómetros de la Tierra. En ambas ocasiones, Ío fue observado moviéndose en la sombra de Júpiter por un periodo de unos 40 minutos antes y después del comienzo del eclipse.

En cuando a Ío, este es el satélite galileano más cercano al planeta Júpiter. Es la cuarta luna más grande, teniendo la densidad más grande de todas las lunas, y es el objeto más árido del Sistema Solar. Fue descubierta en 1610 y nombrada en honor del personaje mitológico Ío, una sacerdotisa de Hera y que se convirtió en una de las amantes de Zeus.

Con más de 400 volcanes activos Ío es el objeto geológico más activo en el sistema solar. Esta extremadamente actividad geológica es el resultado del calentamiento de marea de la fricción generada dentro del interior de Ío mientras es estirado por Júpiter y otros satélites galileanos—Europa, Ganimedes y Calisto. El vulcanismo de Ío es causante de muchas de sus genuinas características. Sus columnas volcánicas y flujos de lava producen grandes cambios en la superficie coloreando a esta de varios y sutiles tonos de amarillo, rojo, blanco, negro y verde, mayoritariamente debido a la alotropía y los componentes sulfúricos. Con un diámetro de 3 600 kilómetros, es la tercera más grande de las lunas de Júpiter. En Ío hay planicies muy extensas y también cadenas montañosas.

Fuentes: NASA, Southwest Research Institute, USGC, Wikipedia

|

| An artist’s rendering depicts the atmosphere on Io, Jupiter’s volcanic moon, as it collapses during daily eclipses. Credit: Southwest Research Institute |