ALMA Finds Unexpected Trove of Gas Around Larger Stars in the Scorpius-Centaurus OB Association

A team of astronomers have used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to survey dozens of young stars – some Sun-like and others nearly double that size – and they discovered that the larger variety have surprisingly rich reservoirs of carbon monoxide gas in their debris disks. In contrast, the lower-mass, Sun-like stars have debris disks that are virtually gas-free.

This finding contradicts the expectations from astronomer, which hold that stronger radiation from larger stars should strip away gas from their debris disks faster than the comparatively mild radiation from smaller stars. It may also offer new insights into the timeline for giant planet formation around young stars.

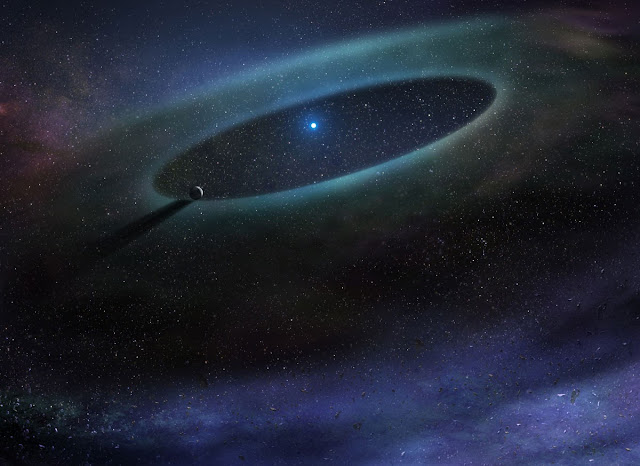

Debris disks are found around stars that have shed their dusty, gas-filled protoplanetary disks and gone on to form planets, asteroids, comets, and other planetesimals. Around younger stars, however, many of these newly formed objects have yet to settle into stately orbits and routinely collide, producing enough rubble to spawn a "second-generation" disk of debris.

"Previous spectroscopic measurements of debris disks revealed that certain ones had an unexpected chemical signature suggesting they had an overabundance of carbon monoxide gas," said Jesse Lieman-Sifry, lead author on a paper published in Astrophysical Journal. At the time of the observations, Lieman-Sifry was an undergraduate astronomy major at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. "This discovery was puzzling since astronomers believe that this gas should be long gone by the time we see evidence of a debris disk," he said.

To find clues as to why certain stars harbor gas-rich disks, Lieman-Sifry and his team surveyed 24 star systems in the area of sky between Scorpius and Centaurus. This loose stellar agglomeration, which lies a few hundred light-years from Earth, contains hundreds of low- and intermediate-mass stars. For reference, astronomers consider our Sun to be a low-mass star.

The astronomers narrowed their search to stars between five and ten million years old -- old enough to host full-fledged planetary systems and debris disks -- and used ALMA to examine the millimeter-wavelength "glow" from the carbon monoxide in the star’s debris disks.

The team carried out their survey over a total of six nights between December 2013 and December 2014, observing for a mere ten minutes each night. At the time it was conducted, this study constituted the most extensive millimeter-wavelength interferometric survey of stellar debris disks ever achieved.

Thanks to an incredibly rich set of observations, the astronomers found the most gas-rich disks ever recorded in a single study. Among their sample of two dozen disks, the researchers spotted three that exhibited strong carbon monoxide emission. Much to their surprise, all three gas-rich disks surrounded stars about twice as massive as the Sun. None of the 16 smaller, Sun-like stars in the sample appeared to have disks with large stores of carbon monoxide. These observations suggest that larger stars are more likely to sport disks with significant gas reservoirs than Sun-like stars.

This finding is counterintuitive, because higher-mass stars flood their planetary systems with energetic ultraviolet radiation that should destroy the carbon monoxide gas lingering in their debris disks. This new research reveals, however, that the larger stars are somehow able to either preserve or replenish their carbon monoxide stockpiles.

"We’re not sure whether these stars are holding onto reservoirs of gas much longer than expected, or whether there's a sort of 'last gasp' of second-generation gas produced by collisions of comets or evaporation from the icy mantles of dust grains," said Meredith Hughes, an astronomer at Wesleyan University and coauthor of the study.

The existence of this gas may have important implications for planet formation, says Hughes. Carbon monoxide is a major constituent of the atmospheres of giant planets. Its presence in debris disks could mean that other gases, including hydrogen, are present, but perhaps in much lower concentrations. If certain debris disks are able to hold onto appreciable amounts of gas, it might push back the expected deadline for giant planet formation around young stars, the astronomers speculate.

"Future high-resolution observations of these gas-rich systems may allow astronomers to infer the location of the gas within the disk, which may shed light on the origin of the gas," says Antonio Hales, an astronomer with the Joint ALMA Observatory in Santiago, Chile, and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Virginia, and coauthor on the study. "For instance, if the gas was produced by planetesimal collisions, it should be more highly concentrated in regions of the disk where those impacts occurred. ALMA is the only instrument capable of making these kind of high-resolution images."

According to Lieman-Sifry, these dusty disks are just as diverse as the planetary systems they accompany. The discovery that the debris disks around some larger stars retain carbon monoxide longer than their Sun-like counterparts may provide insights into the role this gas plays in the development of planetary systems.

Sources: ALMA, Wikipedia

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ALMA descubre inesperadas concentraciones de gas en las grandes estrellas OB de Scorpius-Centaurus

Un equipo de astrónomos usó el Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) para observar un grupo de estrellas jóvenes (algunas similares a nuestro Sol y otras prácticamente con el doble del tamaño) y descubrieron que las estrellas más grandes tienen cantidades sorprendentemente abundantes de gas de monóxido de carbono en sus discos residuales. En contraste, los discos de las estrellas de menor masa, más parecidas al Sol, prácticamente no tienen gas.

El hallazgo contradice las predicciones de los investigadores, que dicen que las fuertes radiaciones de estrellas más grandes deberían despejar los residuos más rápido que las radiaciones más tenues de estrellas más pequeñas. Además, podría dar nuevas luces sobre el tiempo de formación de planetas gigantes alrededor de estrellas jóvenes.

Los discos de residuos suelen encontrarse alrededor de las estrellas cuyos discos protoplanetarios de polvo y gas han dado nacimiento a planetas, asteroides, cometas y otros planetesimales. Sin embargo, alrededor de estrellas jóvenes, muchos de estos objetos recién formados todavía deben adoptar órbitas estables y entran en colisión periódicamente, produciendo suficientes residuos para producir un disco de residuos de “segunda generación”.

“Las mediciones espectroscópicas anteriores de los discos de residuos habían revelado que algunos de ellos tienen una composición química inesperada que delata una superabundancia de gas de monóxido de carbono”, señala Jesse Lieman-Sifry, autor principal de un artículo publicado en The Astrophysical Journal. Cuando se realizaron las observaciones, Lieman-Sifry era estudiante de pregrado de la Wesleyan University, en Middletown (Connecticut, EE. UU.). “El hallazgo fue una sorpresa, puesto que los astrónomos creían que este gas tendría que haber desaparecido mucho antes de que hayan señales de un disco de residuos”, explica.

Buscando pistas que ayudasen a explicar por qué algunas estrellas tienen discos con mucho gas, Lieman-Sifry y su equipo observaron 24 sistemas estelares en zona del cielo entre Escorpio y Centauro. Esta aglomeración estelar dispersa, ubicado a unos pocos cientos de años luz de la Tierra, contiene cientos de estrellas de baja y mediana masa. Como referencia, los astrónomos consideran que nuestro Sol es una estrella de baja masa.

Los astrónomos limitaron su búsqueda a estrellas de entre cinco y diez millones de años de edad (lo suficientemente antiguas como para tener sistemas planetarios y discos de residuos bien desarrollados) y usaron ALMA para examinar las emisiones en longitudes de onda milimétricas emitidas por el monóxido de carbono presente en sus discos de residuos.

El equipo hizo su estudio durante seis noches en total, entre diciembre de 2013 y diciembre de 2014, observando no más de diez minutos por noche. Una vez terminado, era el estudio interferométrico más detallado que se había hecho a la fecha de discos de residuos estelares en longitudes milimétricas.

Gracias a los datos extraordinariamente completos que lograron recabar con estas observaciones, los astrónomos descubrieron la mayor cantidad de discos observados hasta entonces en un mismo estudio. De 24 discos estudiados, tres presentaban emisiones de monóxido de carbono intensas. Para su sorpresa, los tres discos rodeaban estrellas casi el doble de masivas que el Sol. Ninguna de las 16 estrellas más pequeñas y similares a nuestro Sol parecían tener discos con grandes cantidades de monóxido de carbono. De estas observaciones se desprende que las estrellas más grandes son más propensas a guardar grandes cantidades de gas que las estrellas similares al Sol.

Lo sorprendente de este hallazgo es que las estrellas más masivas inundan sus sistemas planetarios con una intensa radiación ultravioleta que debería destruir todo el monóxido de carbono restante en los discos de residuos. No obstante, este estudio demuestra que las estrellas más grandes de alguna forma logran preservar o reponer sus reservas de monóxido de carbono.

“No sabemos a ciencia cierta si estas estrellas están logrando mantener sus reservas de gas por mucho más tiempo de lo esperado o si se trata de una ‘última bocanada’ de gas de segunda generación producida por la colisión de cometas o la evaporación de capas de polvo heladas”, explica Meredith Hughes, también astrónoma de la Wesleyan University y coautora del estudio.

Según Hughes, la existencia de este gas podría cumplir un papel importante en la formación planetaria. El monóxido de carbono es un componente clave de las atmósferas de planetas gigantes, y su presencia en los discos de residuos también podría delatar la existencia de otros gases como el hidrógeno, aunque quizás en concentraciones mucho más bajas. Si algunos discos de residuos son capaces de contener cantidades considerables de gas, el proceso de formación de planetas gigantes podría demorar mucho más de lo que se cree, especulan los astrónomos.

“Con nuevas observaciones en alta resolución de estos sistemas ricos en gas los astrónomos quizás podrían determinar la ubicación del gas en el disco y, de esa forma, entender mejor el origen del gas”, anticipa el coautor del estudio Antonio Hales, astrónomo de operaciones de ALMA en Chile y del Observatorio Radioastronómico Nacional de Estados Unidos, ubicado en Charlottesville (Virginia). “Por ejemplo, si el gas es producido por las colisiones de los planetesimales, es de esperar que sea más abundante en las zonas del disco donde se producen esos impactos. ALMA es el único instrumento capaz de obtener imágenes con una resolución tan alta”.

Según Lieman-Sifry, estos discos de polvo son tan diversos como los sistemas planetarios a los que pertenecen. El hallazgo de que las estrellas más grandes guardan el monóxido de carbono con más celo que sus hermanas más pequeñas y similares al Sol constituye un paso más para entender el papel que desempeña este gas en los sistemas planetarios.

Fuentes: ALMA, Wikipedia