A young supermassive star with a Keplerian disc in the Milky Way

|

| Artist's impression of the disc and outflow around the massive young star. Credit: A. Smith, Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge. |

Astronomers have identified a young star, located almost 11,000 light years away, which could help us understand how the most massive stars in the Universe are formed. This young star, already more than 30 times the mass of our Sun, is still in the process of gathering material from its parent molecular cloud, and may be even more massive when it finally reaches adulthood.

This star is called G11.92–0.61 MM1, a massive young proto-O star and it is an important discovery since the formation process of massive stars is not well understood and it is located, the star is located in the constellation of in Sagittarius.

The researchers, led by a team at the University of Cambridge, have identified a key stage in the birth of a very massive star, and found that these stars form in a similar way to much smaller stars like our Sun - from a rotating disc of gas and dust. The results will be presented this week at the Star Formation 2016 conference held at the University of Exeter, and are reported in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

|

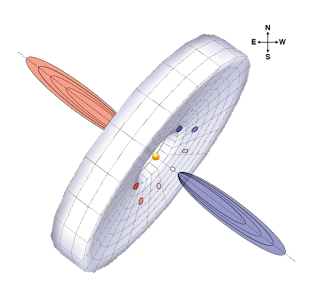

| A proposed morphology for the immediate vicinity of MM1 as viewed from Earth. Credit: Credit: Institute of Astronomy of Cambridge. |

In our galaxy, massive young stars - those with a mass at least eight times greater than the Sun - are much more difficult to study than smaller stars. This is because they live fast and die young, making them rare among the 100 billion stars in the Milky Way, and on average, they are much further away.

"An average star like our Sun is formed over a few million years, whereas massive stars are formed orders of magnitude faster -- around 100,000 years," said Dr John Ilee from Cambridge's Institute of Astronomy, the study's lead author. "These massive stars also burn through their fuel much more quickly, so they have shorter overall lifespans, making them harder to catch when they are infants."

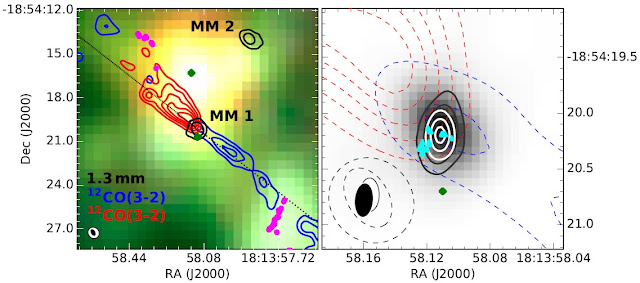

The protostar that Ilee and his colleagues identified resides in an infrared dark cloud - a very cold and dense region of space which makes for an ideal stellar nursery. However, this rich star-forming region is difficult to observe using conventional telescopes, since the young stars are surrounded by a thick, opaque cloud of gas and dust. But by using the Submillimeter Array (SMA) in Hawaii and the Karl G Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico, both of which use relatively long wavelengths of light to observe the sky, the researchers were able to 'see' through the cloud and into the stellar nursery itself.

By measuring the amount of radiation emitted by cold dust near the star, and by using unique fingerprints of various different molecules in the gas, the researchers were able to determine the presence of a 'Keplerian' disc - one which rotates more quickly at its Centre than at its edge.

"This type of rotation is also seen in the Solar System - the inner planets rotate around the Sun more quickly than the outer planets," said Ilee. "It's exciting to find such a disc around a massive young star, because it suggests that massive stars form in a similar way to lower mass stars, like our Sun."

|

| Left: Contours of SMA 1.3mm VEX continuum (black) and blue/redshifted. Right: Zoomed view of MM1. Credit: Credit: Institute of Astronomy of Cambridge. |

The initial phases of this work were part of an undergraduate summer research project at the University of St Andrews, funded by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The undergraduate carrying out the work, Pooneh Nazari, said, "My project involved an initial exploration of the observations, and writing a piece of software to 'weigh' the central star. I'm very grateful to the RAS for providing me with funding for the summer project -- I'd encourage anyone interested in academic research to try one!"

From these observations, the team measured the mass of the protostar to be over 30 times the mass of the Sun. In addition, the disc surrounding the young star was also calculated to be relatively massive, between two and three times the mass of our Sun. Dr Duncan Forgan, also from St Andrews and lead author of a companion paper, said, "Our theoretical calculations suggest that the disc could in fact be hiding even more mass under layers of gas and dust. The disc may even be so massive that it can break up under its own gravity, forming a series of less massive companion protostars."

The next step for the researchers will be to observe the region with the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA), located in Chile. This powerful instrument will allow any potential companions to be seen, and allow researchers to learn more about this intriguing young heavyweight in our galaxy.

Credit: University of Cambridge, Submillimeter Array (SMA) Newsletter, The Royal Astronomical Society, Institute of Astronomy of Cambridge, Wikipedia

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Una joven estrella supermasiva con disco Kepleriano en la Vía Láctea

|

| Sagittarius, field of view where G11.92–0.61 MM1 is located. |

|

Location of G11.92–0.61 MM1 within Sagittarius.

Credit: Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK

|

Esta Estrella se llama G11.92–0.61 MM1, una joven masiva protoestrella O, siendo un importante descubrimiento, ya que el proceso formativo de estrellas masivas no se entiende bien, la estrella se ubica en la constelación de Sagitario.

Los investigadores, dirigidos por un equipo de la Universidad de Cambridge, han identificado un estado clave en el nacimiento de una estrella muy masiva, y descubrieron que estas estrellas se forman de manera similar que las estrellas menos masivas como nuestro Sol - a partir de un disco giratorio de gas y polvo. Estos hallazgos serán presentados en la conferencia Star Formation 2016 a realizar en la Universidad de Exeter, y se informa de ello en la publicación de Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

En nuestra galaxia, jóvenes estrellas masivas – aquellas con al menos una masa 8 veces superior a la del Sol – son mucho más difíciles de estudiar que las pequeñas más estrellas. Esto se debe a que viven rápido y mueren jóvenes, haciéndolas raras entre los 100 billones de estrellas que hay en la Vía Láctea, y de media están mucho más lejos.

“Una Estrella común como el Sol se forma en el transcurso de unos pocos millones de años, mientras que las estrellas más masivas tardan en formarse varias órdenes de magnitud más rápido -- alrededor de 100.000 años,” dijo Dr John Ilee, del Instituto de Astronomía de Cambridge, quien es el autor principal de la investigación. “Además, Estas estrellas masivas queman su combustible mucho más rápido, así que por ello tienen periodos de vida más cortos por lo general, haciéndolas más difícil de ver en su infancia.”

Las protoestrellas que Ilee y sus compañeros han identificado se hallan en el infrarrojo en una nube oscura - una densa y fría región de espacio que la hace idea como guardería estelar. Sin embargo, esta rica región en formación de estrellas es difícil de observar usando un telescopio convencional, ya que las jóvenes estrellas están rodeadas de una densa y opaca nube de gas y polvo. Pero usando el Submillimeter Array (SMA) en Hawái y el Karl G Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) en New Méjico, que usan longitudes de ondas relativamente largas para observar el cielo, los investigadores pudieron ‘ver’ a través de la nube en la propia guardería estelar.

Gracias a la medición de la cantidad de radiación emitida por polvo frio cerca de la estrella, y usando las huellas particulares de diferentes moléculas en el gas, los investigadores pudieron determinar la presencia de un disco 'kepleriano' – uno el cual rota más rápido en su centro que en los bordes.

“Este tipo de rotación se ve también en el Sistema Solar – la planetas interiores rotan alrededor del Sol mas rápidamente que otros planetas,” dijo Ilee. “Es emocionante encontrar un disco así alrededor de una joven estrella masiva que se está formando, porque sugiere que las estrellas masivas se forma de manera similar a las de baja masa, como nuestro Sol.”

Las fases iniciales de este trabajo eran parte de un trabajo de investigación de verano de licenciatura en la Universidad de St Andrews, financiada por la Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). El licenciado que llevaban a cabo el trabajo, Pooneh Nazari, dijo, “Mi proyecto requería una exploración inicial de las observaciones, y escribir una pieza de software para 'pesar' la estrella central. ¡Estoy muy agradecido a la RAS por facilitarme la financiación del proyecto de verano – animaría a cualquiera en el mundo académico de investigación de intentarlo!”

A partir de estas observaciones, el equipo midió la masa de las protoestrella en más de 30 veces la masa del Sol. A parte de esto, el disco que envuelve a la joven estrella también fue calculado, siendo relativamente masivo, entre 2 y tres veces la masa de nuestro Sol. El Dr. Duncan Forgan, también de St Andrews y autor principal de un artículo anexo, dijo, “Nuestros cálculos teóricos sugieren que el disco estuviera de hecho escondiendo más masa bajo las capas de gas y polvo. El disco podría incluso ser más masivo de lo que podría hacer que su propia gravedad no lo rompiese y formar así una serie de protoestrellas estrellas acompañantes menos masivas.”

El siguiente paso para los investigadores será observar la región con el Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA), situado en Chile. Este poderoso instrumento ayudará a que cualquier acompañante en potencia sea visto, permitiendo a los investigadores aprender más sobre estos interesantes jóvenes pesos pesado de nuestra galaxia.

Credit: University of Cambridge, Submillimeter Array (SMA) Newsletter, The Royal Astronomical Society, Institute of Astronomy of Cambridge, Wikipedia